Wildfires are devouring central Chile as I write this, the result of drought, heat, and human carelessness. The government has mobilized firefighting on a massive scale, and the chief concern is securing the safety of people and property. But I find myself thinking about the trees. We have just spent the better part of a month exploring natural preserves within a day’s drive of Pucón. We have seen an astounding variety of old-growth and endemic trees—some as much as 600 years old. One species has been in this tip of the world since before the continents split up. The thought of them being lost seems like a crime against Earth.

The parks we’ve visited are not threatened by the fires at this time – nor are we, as Pucón is 500 miles to the south of the biggest conflagration. Spring was wet here, keeping groundwater plentiful and rivers rushing, even as we’ve had nothing but dry days and sunshine since January began. But the threat of fire is always real, and every park posts signs imploring visitors to not light flames. It’s peak summer now, so there are plenty of visitors, and the more humans, the greater the chance of catastrophe. What we’ve seen mostly, though, is respect.

The araucaria tree caught our attention first. Some call it the “monkey puzzle” tree, purportedly because, when an 18th-century British naturalist brought one back home, a witty observer saw the spikes growing out of its bark and said, “It would be a puzzle for a monkey to climb this tree.” For the record, no monkeys live near this tree’s habitat, so none have ever been seen puzzling out how to climb it. The indigenous Mapuche people call it the pehuén (pay-when) and consider it sacred. When Spaniards first arrived, they originally called the Mapuche people “Araucanos” and named the tree (and eventually the province) after them. Whatever it’s called, this tree took our breath away.

The aurucaria, a national symbol of Chile, is now an endangered species, protected in numerous preserves. It’s technically a pine tree, but without the sweet balsam smell of North American pines. Its “needles” are the most striking feature—bright green, triangular leaves arrayed in a mesmerizing spiral along long, skinny branches. Protective spikes on young trunks eventually give way to thick blocks of bark on older trees, with the rough toughness of dinosaur armor. Lower branches fall off over time, leaving only a crown of green way up, often sticking out distinctively above the forest canopy. Mature trees can be 150 feet tall, 8 feet wide, and 300 years old, though some can live as much as 1,000 years. The average leaf is 24 years old, and the species dates back to the Jurassic period. It has endured dinosaurs, ice ages, and human encroachment—so far.

(click on photos for a larger view)

Signs in one park told us that the Mapuche always ask permission of the pehuén trees when entering their domain. Asking permission demonstrates respect, and it’s a cultural norm in this part of Chile—people always ask, “¿Permiso?” before entering a shop or a home. Entering an aurucaria forest, we felt small and young and noisy. We were guests there. We asked, “¿Permiso?” We stayed quiet, breathed deeply, and occasionally stopped to admire, smile, and listen to birds we have never heard before, like the chucao and the huit-huit, whose calls sound just like their names. We felt the energy of life that began long before ours and will continue long after. Experiencing a Jurassic forest of aurucaria trees is far more than a walk in the woods—it’s a passage through time into an earlier world.

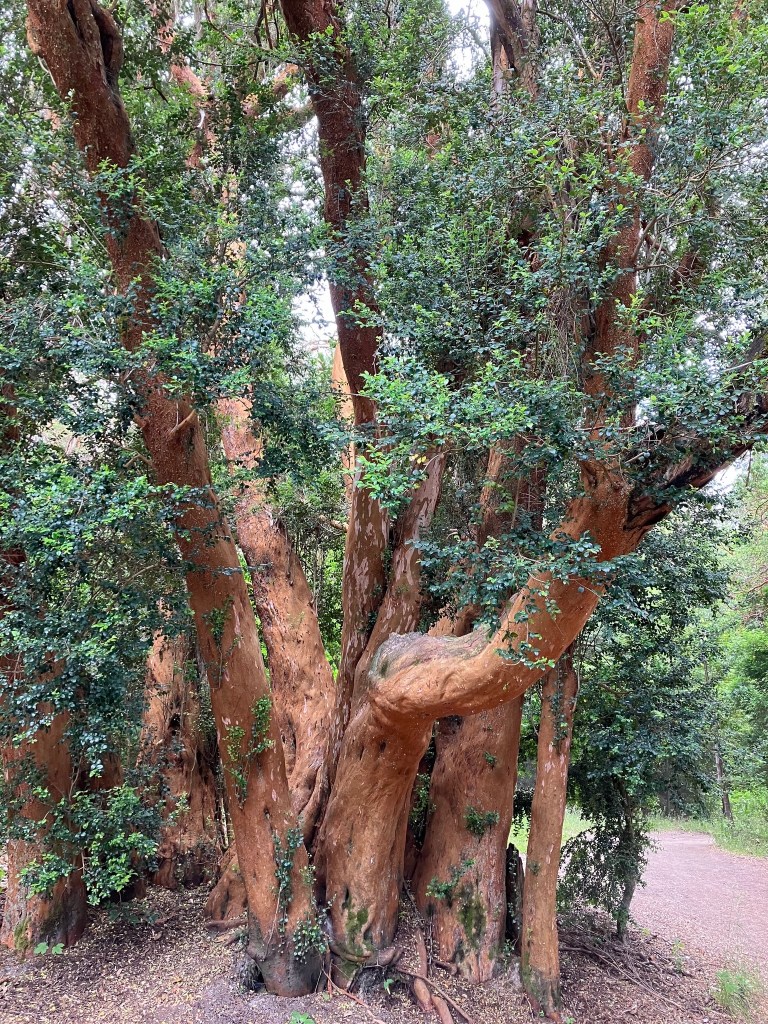

A few hours’ drive from the aurucaria trees is a private nature preserve called Huilo-Huilo (wee-lo wee-lo). A justifiably renowned eco-tourism destination created in 1999, Huilo-Huilo profits from its trees and waterfalls without destroying them. Set in nearly 400 square miles of temperate rainforest, it has a mix of evergreen and broad-leaf trees, along with 25 species of ferns, and gets abundant rainfall (though none when we visited in January). It may be most famous for its unusual hotels, built with, among, around, and under the trees. One hotel is named for the Nothofagus, a genus of tall southern beech trees that fill the park with shade and grandeur. Because they are found in both southern South America and Australia/New Zealand and their seeds are easily damaged by seawater, their existence is considered evidence that the continents drifted apart some 100 million years ago. One species, the coigüe, (co-ee-gay) can reach 150 feet tall, and its horizontal, twisting branches form magical shapes that look like the handiwork of the wood nymphs and elves that, according to legend, live in this forest.

We walked three or four of the trails that snake through the trees and along the river, where a dozen different waterfalls pour over smooth rocks into blue-green pools swirling with foam. One path, El Poeta, features a series of signs with Mapuche poetry about the trees, water, and their role in life by the first indigenous writer to receive Chile’s National Prize for Literature (in 2020). Here’s part of one, translated from the original Mapuche language to Spanish to English (please forgive any language oddities, which probably result from these multiple translations):

I hugged the oldest coigüe

Around which the forest has gathered for so long.

In the ridges of its trunk

I felt the hands of my parents

Of my grandparents

Of the daughters of my children and my brothers

Yes, in the blood of its sap I hear

The conversations of my people.

—Elicura Chihuaila

I admit, I hugged a tree there too. I felt its energy. I wished I could hear its stories. Later, in Parque Oncol, near Valdivia, I hugged another tree. I guess I am now a serial tree hugger. This one has a name: Abuelo Tineo (Grandfather Tineo). It is more than 600 years old and would require six to eight people with outstretched arms to reach around its base. I later learned that Abuelo Tineo also inspired a Chilean cellist to compose and perform an original piece at the base of the tree, incorporating the sounds of birds and leaves in the wind. If you’re interested, you can watch the 13-minute performance here. Fair warning, though: There’s not much traditional cello music, but there is beautiful video of the trees and sounds of the chucao and other birds. If you have the patience of a tree, you will be rewarded.

(click on photos for a larger view)

I was lucky enough to grow up surrounded by trees. We had pines all around our house, and my hands were often sticky with pitch from climbing them. A proud New England maple turned bright red every fall outside my bedroom window. My favorite white birch tree in the world stands lakeside by our little cabin in Maine, catching the afternoon sun in its flickering green leaves. I did not expect to learn anything new about trees on this journey. But here I’ve seen arrayan trees that are cinnamon-colored and cinnamon trees that are not. I’ve seen smooth-barked meli trees that are patched like a calico cat and other melis that are as white as bones. I’ve read that the world’s oldest living tree – estimated to be 5,000 years old – is closely guarded in a park near us here in Chile. Think about it: This tree was sprouting from the ground when humans across the ocean were developing writing. It has existed longer than the Egyptian pyramids. Even Abuelo Tineo, a relative youngster, has been rooted to that same spot in southern Chile since well before the Spaniards arrived here. I don’t think I ever felt the respect that trees are due until now.

In New England, the trees are mostly new, geologically speaking. The trees we have seen in Chile are ancients. They stand tall at the center of a thriving ecosystem, from the animals that live on, under, and inside them to the air plants that grow on their trunks and branches, high off the ground. They are contributors. They are survivors. And when they do eventually die, woodpeckers feed on them and new life grows from them. If that’s not worth a hug, what is?

I love this homage to trees! You’ve really captured something special here. Tree species really do define a place—happy that you are able to spend so much time among—and hugging—them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I used to own a book, “The Tree,” [can’t recall nor find the author’s name]. I loved the book, it was full of data and interesting scientific concepts, like anatomy of trees, growth habits, reproduction processes, etc BUT it lacked poetry. This blog beautifully and humanely complements what I think I know of trees.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Al, thank you for your beautiful, respectful homage to Chile’s trees and to the trees that have made a difference to you personally.

Lane

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Al and Rachel, It’s always wonderful to hear from you, and to enjoy your perspectives from your unusual (I mean that in a good way) venues. I am especially grateful that you noted the fact that you’re far from the wildfires, though it sounds like national botanical garden did not survive the devastation.

You both will be well prepared to put together, after your 10 years of travel, many-paged books full of wondrous sights and unique people you have met along your way.

Thank you in the meantime for sharing some of that with all your admirers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always love your travel reports and particularly enjoyed the latest one about the Chilean trees. I often skied among the araucarias on the slopes of Volcan Llaima near Temuco. Very special vegetation indeed. Now I am saddened, upset and distressed about the damage the Chilean wildfires have been doing. I’ve often enjoyed the huge Chilean National Arboretum near Vina del Mar/Valparaiso, and it’s devastating to read that 98% of its thousand acres have been consumed by the flames, destroying survivals from Rapa Nui such as the Sophora Toromiro plus many more tree rarities.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree, the damage in Valparaiso and environs is so sad, and the botanical gardens a particularly devastating loss. I think I read that its caretakers were also killed. Just terrible.

LikeLike

I was mesmerized by the video of the cellist and the sumptuous views of the trees and sounds of the birds and wind. So grateful for that. Wish Yo Yo Ma could see it. Your appreciation for all you see and do warms my heart.

LikeLike

Thank you Shirley! Glad you appreciated the video — you must indeed have patience!

LikeLike

Ha, not that patient with jigsaw puzzles, especially when all around me are succumbing to COVID.

LikeLike

The trees are magical and your words and pictures allow us to share in their majesty. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person